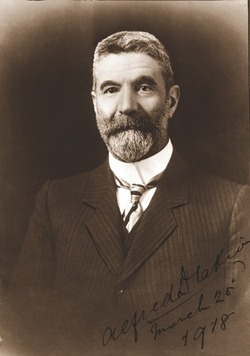

Alfred Deakin was born 3 August, 1856 and died 7 October, 1919. Deakin was the Prime Minister of Australia on three separate occasions: 24 September, 1903 to 27 April, 1904; 5 July, 1905 to 13 November, 1903; and 2 June, 1909 to 29 April, 1910. He was Leader of the Protectionist Party 1901 to 1910 and of the Liberal/“Fusion” Party 1909 to 1910. Deakin represented the electorate of Ballarat, Victoria 1901 to 1913.

Elections contested

1903, 1906, and 1910Mr. Mayor, ladies and gentlemen, electors and electresses of Ballarat—(laughter)—at least once in every three years you are called upon, before choosing your representatives to take a collected view of the position in the Commonwealth, to return upon the past, or at all events upon the recent past, in order that you may be enabled to decide upon and prepare for action in the immediate present. Without a recollection of the roads travelled and the bridges crossed since our union was accomplished nine years ago, we should probably misunderstand the present and misjudge the future. Indeed, the lessons of our experience during the troubles and trials of that time ought to be among the most valuable assets we have derived from them.

No programme submitted to you tonight can be fairly judged apart from some review of those trials and accomplishments, which should place you in a position to obtain a true perspective of the issues to which your thoughtful consideration is now invited. (Hear, hear) But do not misconceive these preliminary admissions. to be an excuse. The absence of time even to summarise these lessons, or draw conclusions, and the number and intricacy of questions about to be submitted to you, require me to rely upon your memory and upon your judgement to supply that complete review which I cannot possibly attempt tonight. Whether, the people of the Commonwealth have yet “found themselves”, in the full sense of the phrase or not, we maybe sure that despite the great distances which separate our scattered communities and the supposed conflicts of interest which arise among us, at least we understand each other much better than we did. (Applause)

We have all of us had much to learn and not a little to unlearn during the process of creating a Commonwealth, but the clear result is that we to have today a firmer foothold, a clearer outlook, a more mature judgement and a deeper sense of nationality than ever before. (Cheers) “Cabined” by the time at our disposal, “cribbed” within the existing situation, and “confined” even in respect of the Government policy to a general reference to our principal measures, I pass to my task. The gradual growth of Federal legislation with the relation of the new measures already passed, would, if it could possibly be conveyed to you in a few sentences, furnish a proper perspective for our programme. As it is, the magnitude of Australian affairs and the wide sweep of their field of influence must, oppress the most robust speaker and the most untiring of reporters with a sense of their inability to compress the details into one speech. Selecting the issues carefully and treating them with brevity, I must remit to the many other meetings in which I shall have an opportunity of meeting my fellow citizens—(hear, hear)—the further and full consideration of certain important problems.

And now, as a last word of introduction, permit me to offer my congratulations to all citizens of the Commonwealth upon the magnificent season with which Providence has blessed us. (Hear, hear) But for one unhappy and unhappily prolonged industrial disturbance, we should enjoy on an absolutely unclouded horizon. But as it is, in Spite of losses and trials, Australia, speaking generally, was never more prosperous, and never enjoyed a more hopeful outlook; than she does today. (Applause)

The Federal past

Since 1901 the Commonwealth has seen three Parliaments. The first devoted mainly to the task of organisation: the second occupied with the struggle between conflicting parties, and the third, while in part devoted to organisation, before its close included in its work. the development of a national policy. The fourth Parliament which you are about to choose should complete our equipment, and before it closes see our Federation launched at last with full powers. In the last nine years we have had seven administrations. During that period we have always had three and sometimes four sections in Parliament. Why parties exist and must exist is plain. Our Federal Constitution, inheriting responsible government, makes two parties essential. There may be minor differences on each side, but in our Constitution Ministry and Opposition must always co-exist.

But a further source of cleavage has been added during our history owing to the Ishmaelitish methods of the Labour party. The Labour members have marked contrasts among themselves. With us differences are tolerated, with them differences are amputated. (Laughter.) Outside of politics they represent the usual varieties of type. In polities they are all obliged to wear the same suits of the same material, the same pattern, the same size, and the same cut. (Laughter) We each of us take the liberty of wearing our own clothes—(Laughter)—but some of our friends of the Labour party make rather odd figures in what are obviously ill-fitting garments. Then again, Labour has two political sides. Inside all are alike, outside an inch or a mile makes no difference. There is absolute labour isolation. The Labour Party thus creates a cross division, often occupies the cross benches, and lately went to them in a very cross temper. (Laughter) At this election, however, there are only parties, and only one dividing line. (Loud cheers) Our constitution requires that, and labour tactics have riveted it upon us.

Liberals vs Labour

In the Labour Opposition there is not a natural and real, but a narrow, mechanical, compulsory uniformity enforced by constant knee drill in caucus. (Laughter) They stand all alike and all apart. The Liberal party stands in a broad unity, but individualities remain. Independence is asserted for ourselves and our constituents. We are associated as public men for public purposes, specific and clear. Beyond them we are free, and within them we are free also. (Cheers) We are united by the policy it is my duty to outline this evening. Our present union is not upon mere projects in the air. Although not eight months old we can afford to be judged by what we have done-in a single annual session. There has been no such record in the history of the Commonwealth. (Hear, hear)

Work of this Parliament

The story of the late Parliament was divided into parts. The first was distinguished by the passage of a revised tariff, on an accepted principle. On the opening of that Parliament the leader of the Opposition agreed that the verdict of the electors had been decisive. Speaking on February 21st, 1907, he admitted that the result of the election was a distinct adoption of the protectionist principle throughout Australia. That being approved, our schedules were shaped upon it. There were errors of judgement, there was imperfect information, there were inconsistencies and unsatisfactory compromises. Still a great task was accomplished, with great pains. The general fiscal lines were laid down, though imperfectly realised.

The next great piece of organic legislation in that Parliament was the passage of an Old Age Pensions Act, with the support of all parties on both sides. Experience is now testing that measure and its estimates. It will probably be the basis for further operations in similar directions now under study. The third memorable achievement, now superseded, was the Surplus Revenue Act, an important declaration of the meaning of the Constitution. A fourth authorised an iron bounty, establishing one of the fundamental industries which this continent requires. The fifth great task was to provide for coastal defence, £250,000, an appropriation accomplished only with great difficulty, with great resistance and upon a solemn Parliamentary pledge as to the conditions of its expenditure. All these measures were the work of the first Ministry that held office during the present Parliament.

Work of Ministry

Passing over a recess Cabinet to the third Administration, which commenced its life at the opening of this session, I may be pardoned for reminding you of the strange and most unpromising circumstances under which we began. We were to be met with war to the knife. We were not to be allowed to pass one measure. One of your local representatives assured us that we would not be allowed to “dot an I or cross a T” during our existence. It was to be made the poorest of all sessions, yet it proved to be the richest both in the number and importance of the measures passed. There was an amendment of the Old Age Pension Act, to enable pioneers of foreign birth who had neglected to naturalise to obtain 1 the boon.

A bill founded our naval defence. (Hear, hear) Another great measure dealt with land defence—(cheers)—and another, establishing the High Commissioner’s office, was followed by his appointment. Then there was the passage of a bill establishing the seat of government, an Electoral Bill, simplifying and cheapening procedure, an Australian Coinage Bill, promising a profit of from £50,000 a year. Another Anti-Trust Bill, a Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, a Seamen’s Compensation Act, a Patents Act, a Bills of Exchange Act, a Marine Insurance Act. These are among the triumphs of our crowded session. (Cheers) They are sufficient for the Government and this Parliament to appeal to the country upon. But the greatest questions are still to be named.

From the list read I have omitted the two measures of the session, one of which aroused the greatest amount of feeling, evoked the longest debate and provoked the deepest interest throughout Australia. (Hear, hear) Both differ from all other measures, because although passed by both Houses of Parliament by statutory majorities, they are not now law. They cannot be law, even by the assent of the Governor-General or of his Majesty the King, until you, at the forthcoming election, by a separate vote at a referendum on each, choose to approve them. (Cheers) Without your sanction they remain waste paper. That of itself should be sufficient to commend them to your deepest thought and your most careful consideration. (Hear, hear)

No statement of policy can approach completeness in which financial issues are not fully dealt with. We depend upon the revenue we have or can make available for what expenditure we can meet, or even propose. But owing to the special position occupied by these bills, which cannot reach the Governor-General until they have passed through your hands, the financial position of the Commonwealth cannot be forecast as usual. Their passage or their failure to pass would create two absolutely different financial situations. On this account, and also because I find myself over-weighted with important questions tonight, I am obliged to postpone an examination of the financial situation, as a whole and in its ramifications, until a later meeting. I then propose to devote a considerable portion of time to the discussion of the merits of the two measures, now in the position traditionally ascribed to Mahomet’s coffin—hanging between earth and heaven.

You will remember that on the formation of this Government the utmost we hoped in respect to future finance after the Braddon clause expires was a temporary arrangement preliminary to a satisfactory and permanent settlement. But when we had sufficiently impressed the representatives of the States with the needs of the Commonwealth and the necessity for allowing it untrammelled authority in such great issues as that of national defence, we were unexpectedly enabled to reach what we believe to be a satisfactory and permanent settlement. You know the rest of the story. You know that this Government, after drafting what is known as the financial agreement, became responsible for passing it through both Houses of Parliament. It has left our hands. It is even out of the power of parliament to touch it. Candidates on any platform are unable to affect it. You, and and you alone, by your votes to be cast at the two referenda at the forthcoming elections, will decide the fate of these two great measures. You must vote “Yes” or “No.” We ask you to consider them from an Australian standpoint, and to vote “Yes.” (Cheers; voices, No, No; and more cheers) Remember, you are asked to consider them from an Australian standpoint, and to vote as Australians. Providing that is your guiding principle, we have nothing to fear. But on this subject I shall have a further opportunity of speaking shortly.

Twin measures

You may say that I have spoken throughout of two measures, and have so far defined only one of them. That is true. It is not because the second is of less importance than the first. They are twin measures—siamese twins. The second is simpler. It authorises the Commonwealth to take over the management of all the State debts which we are not already authorised to take over. This will enable the issue of a single Commonwealth stock, instead of having six State stocks upon the London market; and, in the opinion of the highest financial authorities, my colleague, Sir John Forrest and I myself have been able to consult in London, will ultimately mean an enormous saving to the taxpayer of this country in the interest upon borrowed money and money still to be borrowed. (Cheers.)

This bill in one striking way differs from all constitutional amendments likely to be made for a long while. And why? Because it passed both Houses of Parliament with the unanimous assent of all parties and all members, before being sent on to you. Surely it needs no further recommendation now. It could receive none higher. A Commonwealth Royal Commission will be appointed shortly to advise upon the control and methods of future borrowing in your interests as taxpayers, and in the interests of all the Governments which depend upon you. (Applause)

Future measures

Let me now leave the past, or almost leave it, for the future. Turning from the list of measures already sanctioned, I look at three proposals brought forward last year which still carry forward. The first is the Inter-State Commission Bill, a rather bald title, though in it lies, as I shall endeavour to show you, a series of the most grave and far-reaching proposals ever embodied in any piece of legislation submitted in this country. After the Inter-State Commission Bill there is the Northern Territory Agreement which the Senate declined to pass. There is also the bill for a Federal Agricultural Bureau. Then, to come to proposals, which were ready for submission, but not actually tabled. The first will deal with tariff anomalies. (Hear, hear) The next has relation to preferential trade agreements; and the next to the railway to our great, rich, but not by any means wild, West. Other measures will deal with electoral reform, with the taking over of lighthouses and minor subjects.

A far-reaching bill

The Inter-State Commission Bill, when it reached the Senate, received a careful review, but there is even now an imperfect appreciation of what this measure is capable of accomplishing. The supremacy of Parliament in this country is not only unchallenged, but unchallengeable. Its authority within the limits of the Constitution is unquestioned. But that authority cannot be exercised by Parliament as a legislature. In order to accomplish its tasks, it requires a potent executive, to give effect to its will, supported by a public service of officials who are well trained and competent men. To this administrative organisation, more and more thought on your part will be required, because if its machinery goes wrong the best legislation in the world can be of little effect. Just as you, the electors, delegate the supreme authority vested in you, to Parliament, retaining in your hands the power to make and unmake Parliaments, so Parliament in its turn delegates to its agencies many powers of many kinds, which it may recall or expand. Parliament debates and decides policies, but the hand with which it acts must be that of its potent executive, controlled in a constitutional manner.

Powers of the Inter-State Commission

Our Inter-State Commission Bill covers a series of proposals for more effectively equipping Parliament, first with knowledge, and then with power. It embodies more proposals for research and adjudication than have been included in a single measure in this country. This is essential, because the tasks of Governments are always on the increase. We require to avoid two things – on the one side, an insufficient establishment, since that leaves the Government helpless, and on the other side, a bureaucracy eating up in mere machinery what was meant to accomplish public purposes. (Cheers) In endeavouring to find a path between these two risks, we have attempted in this legislation to provide for an effective review of the working of our legislation to impartial critics, who will report to Parliament on any matter which it may be necessary for it to consider. In order to prepare a policy or alter its machinery for carrying it out, Parliament employs at one time a Royal Commission, at another time a Select Committee. We have also to deal with many subjects which do not require a political colour, benefit by being kept apart from politics, which are not partisan, and require expert knowledge. Parliament will find the policy and its agencies will find the facts.

A knowledge of the facts of today—of the current realities amongst which our legislation has to operate—is recognised as a modern necessity. The first nations of the world in executive efficiency are those, which, like the great Empire of Germany, have built up most perfect machinery for obtaining information on the great processes of national and industrial life. When they know these they are equipped to undertake great national tasks. The plea for an Inter-State Commission is because we greatly need a clear and definite knowledge of facts of the operations of our statutes and of the departments administering them. This is essential if a government is to do its business efficiently. At present our Parliament is insufficiently fed with the facts relating to the great social, fiscal and industrial issues which lie around us and lie before us. The most rapidly expanding department in the mother country is the Board of Trade, which has been of late rapidly adding to its former functions some of which I have been describing. That Board commands the services of independent and well qualified experts who examine into the conditions of trade, labour, and industry, wages, hours, and all other circumstances that Parliament ought to know with accuracy. When armed with such know ledge, a Legislature will be, for the first time, completely fitted for its modern task. There is a wide range for these inquiries, whose results are most valuable t employers and employed, and essential to all public men. When fully armed with accurate knowledge and experience our Legislature will for the first time be completely fitted for its new tasks. Let us apply that doctrine.

The fiscal question

There is the fiscal question. It pays nowadays to study. (Hear,hear) It pays, to know. For those who don’t study and don’t know in private life there is the refuge of the Insolvency Court; in public life there follows national disaster. (Applause) May I ask you to apply that doctrine to the fiscal question. (Hear, hear) On no subject is there more need of clear light and unimpassioned testimony. This is proved by the recent decision of the most intelligent business Parliament in the world, the United States Congress. On the the insistence of President Taft that Congress has given him a Foreign Tariff Board. Mr. Mauger has lately quoted the President’s statement of the purpose of that Board. It is to tell Congress at any time the full facts and exact circumstances affecting the cost of production, the cost of freight and the cost of labour in connection with the goods made in the country or that come in to competition in the United States with the goods produced there. So armed the President and his Congress will be capable of dealing with the tariff as a tariff ought to be dealt with, and will be dealt with in Australia before long—as a business proposition apart from abstract theories and general political controversies. ( Applause)

We have had the business needs of the country before now put at hazard in the strife of parties. We have not had a clear light, an indisputable knowledge brought to bear upon the facts, including all the intricacies of exchange or of combination or competitive powers. This Inter-State Commission should be composed of impartial, capable, faithful, independent men, who should study and certify to Parliament the conditions of our industries, the conditions under which men and women work in our industries, the conditions under which goods are brought in to the country of the same class as those made here. We should know whether the contest is really between superior ability and machinery or between sweated labour and the labour said to be fairly paid. (Hear, hear)

Half the time spent in our tariff debates would have been saved if we could have had undoubted facts before us. Half the delay that occurs in these matters arises out of our imperfect knowledge of our own conditions and those of our rivals, and through insufficient technical information to enable us to discriminate between them. Protectionists themselves have over and over again been gravely divided because of disputed facts. (Mr. Manger: Hear, hear)

Wholesale revisions of the tariff will, I trust before long, become things of the past as far as the Commonwealth is concerned. (Hear,hear) When the clear light of knowledge is thrown upon all points in dispute we ought to be able to deal with these questions without political or party convulsions, or the stoppage of other legislation. The manner in which we can best do justice to the workmen and employers and industries of Australia is to assure ourselves that we have got the facts and nothing else before us. (Hear, hear.)

We should always keep a finger, on the pulse of trade. We need to watch the legislation and inventions which have led to industrial progress in some European countries. Our Young and nascent industries, scattered over the vast territory, should be enabled to maintain themselves against the shock of unscrupulous or unfair competition.

Our tariff will have to be dealt with on a business basis.

Early removals of anomalies

We are faced to-day by anomalies. (Hear,hear) Some of them were intentional, that is to say, they were deliberately made by a vote of Parliament, others were unintentional, and a few were due to a mixture of both. We will do our best to supply any deficiency of information. Though it is not proposed to wait for the establishment of the Inter-State Commission and the full working of the new system, you will at all events find that when the result, of the examinations which have been proceeding for some time by the Minister of Customs are brought before Parliament our proposals will be based upon more matured judgement than any heretofore submitted. (Cheers)

The Government stands fully seized of the importance, not only of dealing with anomalies as early as possible, but of the importance of dealing with them so far as possible on a somewhat new plan, as questions of L.S.D. affecting the people of this country, as business proposals. (Cheers) The policy of the Government in that regard has not been changed one iota from the agreement published before it came into being. It was specially stated that this Government proposed no interference with the protectionist policy of the country, and that the rectification of anomalies of anomalies would be undertaken on the lines of the existing tariff and following the same pattern. (Hear, hear)

Preferential treaties

Fiscal information will also assist us in the beneficial area occupied by reciprocal tariff concessions from one dominion to another. We have good hopes that during then ext session Parliament will have before it proposals for preferential trade agreements with no fewer than three of the dependencies of the Empire—two with Canada and New Zealand, with whom we have not yet succeeded in coming to terms, and one with South Africa, with whom we already have an agreement, to which they desire to make an addition.

It will be our endeavour, as it has been already our aim, to make these preferential treaties a means of cementing the British Empire. We are pursuing a closer study of the preferential advantages which we have conceded unasked to the mother country, in order that they may be made more effective when a proper occasion arises. (Cheers)

The importance we attach to the fiscal question arises from its direct relation to the employment of our people, the employment of local capital, the development of the sense of national unity, and of that great national spirit by which I believe the whole of his Majesty’s dominions are now becoming inspired. There is need that this should be aroused. There is grave need of unity that in times of peace we should prepare for seasons of strife, becoming bound together by the closest and most intimate reciprocal relations in trade, as well as in all other matters. (Cheers)

New protection

I must now pass on to the great issues relating to New Protection. These also depend very much upon our ascertainment of all the facts surrounding our industries. New protection, as you know, seeks to secure fair conditions to all those employed in industries which receive the care of the State. I now use the word “care” in a wider sense than “protection,” because we propose that the new protection shall not be limited to “protected” industries. They have, perhaps, the first claim, but we desire to establish fair conditions in all industries in Australia whether subject to fiscal protection or not. (Cheers)

Fair hours, fair wages, and fair conditions of employment are now seen to be matters of grave national concern. (Cheers) Australia is a continent, but the Australia we serve consists of the Australian people and those who shall spring from them. Australian industries awake our enthusiasm, not for the sake of the machinery, not because of the money invested in them, but because they are the means of livelihood to and advance the interests of scores of thousands of our fellow citizens. (Cheers)

We look to commerce, we look to industries and machinery, because we see through them to our own people. The new protection aims at bringing home to the electorates, what those who are responsible for the nation’s destinies realise, that these depend upon the numbers, health, efficiency and culture of the people of Australia. On them and on nothing else. We may be in machinery and material possessions the wealthiest nation in the world, yet the weakest in manhood and womanhood if our masses are stunted or morally and mentally starved. My hope is to see every industry in Australia with its wages board—(cheers)—and an arrangement to prevent unfair industrial competition between possibly different verdicts of different wages boards in different States. We must take care that no State suffers because of its establishment of wages boards owing to a lower condition of employment in other States, or elsewhere. (Cheers)

Our aim is to see an independent, impartial and qualified tribunal, preventing injurious conflicts between the decisions of the several State wages boards, so as to secure throughout Australia a complete scheme for the lettering of industrial conditions.

We have the Opposition plan, but what is it? A scheme for governing industrial conditions all over Australia from some one centre, ignoring local conditions, making no adequate provision for local administration. A scheme for legislating without a full knowledge of its effects in the widely differing districts of this enormous continent. That is certain to fail.

It would be enormously costly. It would have an iron uniformity. The circumstances can only be adequately met by a complete system of industrial self-government, and not by an ukase from some central authority seeking to cover the whole of the Commonwealth.

The States have offered their own volition to connect their wages boards under the jurisdiction of a supreme Commonwealth tribunal, authorised to deal with cases of unfair Inter-State competition. We have every hope that the change will be effected this Parliament. If not, we shall ask the people to give us that authority direct. I have no reason to suppose that this step will be necessary. On the contrary, I feel sure that a policy of decentralisation and mutual adjustments will appeal to the whole community.

Unemployment and insurance

I have no more time to speak of the functions of the Board of Trade except to remind you how much is being done in England by reports based upon inquiries into the circumstance’s of unemployment in different parts of the country. In our Inter-State Commission Bill we contemplate not only such inquiries as are made by the Board of Trade in Great Britain, but others more complete. Even in this new country we are face to face with the question confronting every civilised community and shall be with the whole of the problems associated with want of employment.

We have to realise that unemployment, if continuous, not only discourages a man, but disqualifies and finally demoralises him. A good deal can be done, perhaps, in Great Britain, by means of their bureaux, which enable a man to see in what part of the country there is employment and learn in what part of the country there is employment for such as he.

In this continent the problem is very different, because of our much greater area, but yet we hope to do something, and by way of beginning. (Hear,hear) It is difficult to find out, among other things, how much unemployment arises through no fault of the man himself.

If we are to cope with this evil we must consider a variety of causes, as well as consequences, that need expert hands to touch with any hope of success. In a modest way, but persistently and determinedly, we hope to begin the task. (Hear, hear)

We desire that this Inter-State Commission should among other things inquire into the idiosyncrasies of unemployment in Australia—to find out and ticket the man who will not work, and also the capable man who cannot get work, for he is the man we hope to assist. If it were possible to cope with the unemployment of the latter class by means of a system of insurance, we should be happy to do it, but that is a grave question. We have happy illustrations of its operation in other countries, but we must study our own conditions. I venture to say, however, that through these social and industrial matters we are touching the homes and the hearts of our people. We expect this Inter-State Commission to operate sometimes by means of the powers locked up under the word “insurance.”

We cannot overlook the splendid work of our friendly societies. (Hear, hear) We believe much in the way of social amelioration can be done by Government inquiry in connection with them, with perhaps new agencies, Government supervision, and if possible Government aid.

Federal service insurance

When I spoke of Old-Age pensions as a basis, I had this and similar problems in view. Among other things, the insurance of members of the public service requires to be taken into account. We are laving the foundations of a naval and military system, in which it is of the very essence of their employ that superannuation be enforceable as soon as lack of efficiency is exhibited. That, without some provision for the honest employee, is unthinkable. Contributory schemes for the whole service were laid before a previous Government, and will come under our consideration. In our opinion, a way should, and can, be found for a system just to the taxpayers and to the service. I throw out one suggestion.

Federal co-operation

There can be no objection to the States joining hands with the Commonwealth in any matters of this kind, first in regard to the public service, and eventually in a larger field. We have commenced with old-age pensions. But the problems of unemployment knock at State doors, as at ours, and, indeed, they are all doors into the same national house. Why should not the several Governments of Australia accomplish on a wholesale scale, some of these great requirements which task both the Commonwealth and the States?

You are electors both of the Commonwealth and the States. Why not use both your agencies jointly for business purposes and economies. We shall approach these problems as real issues. Where the facts are found, Parliament will find the policy. I have not yet touched on all the functions of the Inter-State Commission. There are many great tasks better known because conferred upon it in our Constitution.

It is a federal necessity. It will give good value for its money, performing many most useful services besides those just indicated, in relation to water supply, railway development rates, and Inter-State trade, which are already specifically remitted to such a body.

Agricultural Bureau

In our Agricultural Bureau, the aim is to co-ordinate, but not to supplant, State efforts. There seems to be an ineradicable superstition that the Commonwealth can do nothing in this way except at the expense of the States. In point of fact, the Agricultural departments of the States must come first in the eyes of local cultivators. But there is a certain amount of duplication, and in other cases local efforts leave things undone, each State waiting for another State to take them up, because what is everybody’s business.

Such things, common to all or some, will become either in part by co-ordination or in the whole, and often by request, the business of the Commonwealth. The Agricultural Bureau is intended to deal with problems which belong to all the states, and from some of which each State shrinks, awaiting the others. Australia should not continue that game of beggar-my-neighbour.

The employment by the Commonwealth of half-a-dozen experts, paid good salaries, masters of diseases that decimate stock or destroy orchards or crops, and of the pests that prey upon them, will not, interfere with the States, which have abundance of these and less general burdens upon their shoulders already.

Difficulties, facing the whole, or large parts, of this country, are great national questions which a great national bureau can deal with. We must multiply our products and their their yields to the utmost. With the State departments co-ordinated, the results of the bureau be a benefit and increased prosperity to the country. (Applause)

Do not mistake me. I am not pleading for unification in this or in anything else. I am pleading for something that will give more than the benefits of unification, without its costs and risks. I am pleading for united action in agriculture and every other pursuit.

The sugar industry

We propose to appoint an important Commission to deal with the sugar industry. We have paid in bounty £1,800,000 to secure white labour, but do not be shocked. Australia has received back twice that amount. The sugar Industry has paid us double the amount of the bonus. We hope soon to be free from the financial, stumbling blocks in regard to this industry, and thus deal with it in more freedom.

It is one of the most important industries in Australia. We have proved that it can be carried on with white labour, and sugar is not the only industry, tropical and sub-tropical, with which we propose to deal. Australia has great territories in the north which can only be utilised by the growth of such products. In regard to the Northern Territory, our aim is to settle it soon, and thus protect its port. You can only do that thoroughly by the construction of a railway. It is a part of Australia which is separated from you in Victoria by a line on the map, because it belongs to another State. That apparent division is only on paper. This is one continent. It has one destiny. We must hold it all.

We have not at the present time enough people there to enforce their claim to the country should anyone else step in. Settlers must be able to maintain themselves by labour appropriate to the country. We have already paid £20,000 to develop the iron industry, and some few thousands to develop the agricultural industry, chiefly of the north. There is much more to be done in this way. We shall require more people and more products there. The white man’s burden here is to make a white man’s country of our northern areas. It is our business and our necessity to attack agricultural and pastoral problems with all the resources of science.

Land defence

Now, by a rather abrupt departure, I come to some of the great work of the last session, which needs to be followed up earnestly, energetically and laboriously. For the first time in our history Australia has laid firm foundations for her own defence by land and sea. (Applause)

In our universal service, we have given a lead to the whole empire, followed a few weeks after in New Zealand, and to be followed, as I hope and believe, by the other dominions, and even, in her own good time, by the mother country herself. The scheme is not complete, but is fundamental and permanent so far as it goes.

It will go much further when our experience is riper. In land defence we are doing well. We are enlisting all the young men of the Commonwealth, organising and equipping them in the most approved manner for the service of their country.

By a most providential occurrence, just as we have passed our Act, and are facing the heavy task of putting it into force, we have the enormous good fortune to be visited by the most experienced organiser of armies, that the British nation possesses to-day. (Cheers.) I cannot express our indebtedness to that great soldier for the patience and thoroughness with which he has devoted himself since his visit— (A Voice : But he was paid for it) He does not receive a single farthing from the Commonwealth, and he gives us services which money could not purchase. (Loud Cheers)

Hitherto the organisation of our naval and military forces has been always confused by conflicting advices. We have been hampered at every step in our naval and military development because we have not at any time had with us a man of such supreme and commanding knowledge that a Government could rest unhesitatingly on his findings. We have had, many competent counsellors and able professional men, but they have not agreed amongst themselves, and so unhappy politicians have had to choose between the advice of experts, all of whom had some authority.

Today we have the highest authority, wise judgement, backed by experience and knowledge, who will present us with a scheme acceptable in its principles, practical in its plan, economic in its cost, and, above all, efficient. Australia will then realise it’s inexpressible obligation to this great soldier who, from love of his country, has put his services at our disposal. Larger areas are required for rifle and artillery ranges, and we are in communication with all the States on the matter.

Owing to the generous action of the New South Wales Government a thoroughly suitable manoeuvre area in that State has been agreed upon. Besides that we have an ammunition factory under contract, a rifle factory, a military college, a school of musketry, and a cordite factory. The site for the military college will probably be found at the seat of Government.

We hope to be able to use a part of the site of government area, which is excellently suited for the purpose for raising our own horses. We Shall also be able to supply some horses to the Indian army, and thus reduce the cost of our own artillery horses to something nominal. (A Voice : What about more rifle ranges?) The matter is being pushed on all over Australia.

Naval defence

In the history of our naval defence there was first, the visit of the American fleet, which gave us a splendid object-lesson of naval power. Next there was our offer of a Dreadnought—(applause, groans, renewed and protracted applause)— the offer of a Dreadnought, which springing from us in the hour of Imperial anxiety sent echoes all round the world.

We had the idea first, but New Zealand anticipated us in action. After the Dreadnought offer came the Imperial Defence Conference, which gave us a plan of united Imperial action. We followed it with our order for the construction of our Fleet unit. Now comes the putting together of the first Australian destroyer. Next will follow the establishment of a naval college in Sydney, built by the generosity of citizens. We have also to hasten the development of our mercantile marine. As compared to the squadron which has been allotted to Australia for the last ten or fifteen years, the fighting strength of our new Australian naval unit of the Eastern fleet will be as 70 to 50.

The extra cost to us will be less than a quarter of a million a year, and the vessels will be Australian owned. It is true we will have raise a loan for its construction, but are pledged to pay it off in a short period, not as an ordinary loan, but by sinking fund of at least 5 per cent., with anything additional that our finances will allow.

Immigration and the states

On the question of immigration I shall say little. It is too late tonight. Recently we revised the whole of our advertising methods in Great Britain, arranging for the regular publication of Australian news, and are hopeful of good results. We are also lending encouragement to the generous proposals made here and and elsewhere for establishing farm schools for the training of youths who desire to become settlers on the land.

Our effort will be to operate with the States, but not necessarily in the same form with each. For instance, Victoria has communicated with us with regard though the special subject of obtaining settlers for irrigation farms. Needless to say, the Commonwealth will offer every assistance.

My own belief in the possibilities of irrigation, and my own knowledge of what we in Victoria have lost by 25 years of delay, will urge that forward. If the other States do not want that class of settlers we will seek the classes that they do want. If immigration is to be undertaken we wish to bring the States into line, and add our weight to theirs, in order that by joint effort we may rapidly obtain a supply of settlers who will add to the wealth of the community.

National expansion

The question of national expansion must come more and more before you when, looking at questions from an Australian standpoint, you put aside for the moment your many State aims. If we are to act continentally the first thing we have to do is to feel and to make this country one. Lord Kitchener has said if he had autocratic power he would make trunk continental lines. I shall be disappointed if before this Parliament closes railways to Perth and Port Darwin have not been sanctioned by Parliament. There are questions of route, there may be questions of terms, there must be questions of conditions, but Australia is not herself — Australia is a severed country— until we tap our north and west, and not too far off in the future our north-west, so that by radial lines inside, as well by naval units outside, we are prepared to to guard our country.

We are fast preparing the seat of Government for occupation, and we can point to the good use being made of our only possession—Papua. Leasehold settlement under improved conditions is proceeding apace. The natives are under more control, and are showing greater willingness to engage in agricultural labour.

The prospects of Papua are at present most hopeful.

Problems of the Pacific

While we have many important interests in the Pacific, we have no jurisdiction. We are entitled to share to some extent the mother country’s sphere of influence, but facing foreign powers, coloured populations, and a condominium with the Colonial Office as well as the Foreign Office to communicate through, we move in a network.

Still more questions with regard to the Pacific have received a great deal more consideration than might be supposed.

Wireless telegraphy

Wireless telegraphy is to be introduced, so that in addition to the cable which already touches Fiji, communication will be provided with those groups of islands in the Pacific like Papua, which are being rapidly settled.

The system is proposed to be extended till a system of communication obtains, which will necessarily add to the trade and intercourse between Australia and the islands to the East. Then, again, among these enterprises is the “all-red” cable route, now to be carried through Canada by a land line under the control of our Cable Board.

The all-red route by sea has not been forgotten, since in conjunction with Canada, we are inviting tenders for a new and quicker service to Vancouver.

We have gained the authority of Parliament to establish a High Commissioner’s office, and have appointed a most able and experienced representative of the Commonwealth. He will deal with questions of immigration, finance, and matters relating to defence, bringing Australia into closer relation with the governing powers at home than is possible by correspondence. Imperial co-operation is the hope and mainstay of the British Empire.

Drastic postal reforms

What we term the Post and Telegraph Office is really an enormous industrial undertaking, without which our everyday and social business relations would be impossible. In this regard it appears clear that our present methods of administration have been outgrown by the extension of the Commonwealth. We propose a reorganisation of the Postal Department, which will probably prove of a drastic nature. Both the Central and State administrations are to be recast. Postal rates and services are to be revised with the object of assimilating charges throughout Australia.

The more remote districts of the Commonwealth are to be given improved facilities of communication. But we cannot make extra concessions without remembering that there must be an extension of telegraph and telephone facilities, more particularly in remote country districts. That has become a necessity of the times, though other concessions cannot be postponed. It is now necessary to supplement our annual outlay by a capital expenditure on developmental works to provide for which we may follow the methods in England, using terminable annuities, which are repaid in a short period.

Australian administration

When I speak of the enormous growth of our executive responsibilities, you must remember that when an act is put upon the statute book that is not the end, It is only a beginning.

It means administrative action, often elaborate, complicated and expensive in character, and almost always permanent. We are doing our best to make ourselves self-dependent. Activities on the part of the Government such as we are undertaking mean a continuous advance, not only in the sense of progressive establishments, but in the cost of the army of permanent employees who carry them out. Administration of an effective and reasonably economic nature is one of our greatest future problems. Here, as elsewhere, we must find men of special executive ability to carry out the great undertakings required of our public services. The universal training we propose for Defence demands great expenditure and effort, but it is essential to national safety, and is a work which we cannot neglect or delay.

We are doing our best to make ourselves self-dependant.

Other work for Parliament

The next Parliament will be by no means idle. We have to pass the new Naval Bill, and a bill for electoral reform providing for majority rule, which was held over from last session. Then there is the Navigation Bill, a measure of great magnitude, upon which we have arrived practically at an agreement with the mother country; also a bill to deal with the Trusts and Combines when their operations are inimical to the interests of the public.

There is a measure in regard to Foreign Companies; another codifying Banking laws; another dealing with Corporation, Trading and laws; another dealing with Corporation, Trading and Finance, and Insolvency.

These do not sound inviting subjects, but to business men they mean a great deal, and indirectly they affect you all. We have therefore with those measures previously enumerated a splendid programme of legislation on modern lines ready for submission to Parliament.

We have plenty of practical legislation ready, among which those gripping industrial problems are prominent.

Among our new measures will be those designed to encourage an expansion of the productive powers of this country, in country and in town. They will have the support of a sympathetic administration. We trust to the delegation of local governing powers everywhere, and rely upon the patriotic spirit of the people as a whole to assist in these ambitious undertakings.

Such a summary, however brief, surely presents fresh thoughts and fresh horizons to your view.

What I have said will at least give you some outline of the grave responsibilities which are incidental to our magnificent heritage’s, Imperial and Australia.

Party of union

Now in conclusion, despite this long record of work done and projected, I am sure that one and all of you realise that independently of this we are facing an entirely new situation.

The present Government is founded upon a union of parties. (Cheers, and some dissent)

Some of our causes of contest in the past have been closed, and others have been transformed. Into many of them, as I think you will agree, too much of the political spirit was imparted, perhaps unconsciously, by both sides.

We made that union of parties without the sacrifice of a single principle—(Cheers)—and today without any sacrifice we continue our policy of practical work. (Cheers)

Not only do we hope to see our agreement maintained, but we hope to see it enlarged.

What took place last session you know. How it began, how it was conducted amidst threats and strife you will remember. (Applause) By ignoring trifles and concentrating ourselves on business, we concluded a more united party then we had begun.

We ignored our more or less artificial or inherited differences.

We went straight on. We. won all along the line.

We intend to go straight on still. (Cheers)

There is no present rift within the lute and there is no mechanical pretence of conformity.

We enjoy our individual judgements as before.

If we have differences of opinion they are allowed.

We shall test them, not by shibboleths, but by their effect upon the interests of the country.

Our union has been public, and it will publicly continue.

It took a good deal to bring us together, but now we are together it will take a great deal more to separate us. (Loud cheers)

We march to the same music. In this Government and in this party no man has parted with individual judgement or his responsibility to his constituents.

We enjoy a proud sense of free union, with free men in a free party.

I look for a further extension of the spirit of natural unity—

(A Voice: Wreckage; Counter cheers and interruption)

Your wreckage we left behind us, as wreckage will always be. (Cheers)

It is now out of sight over the horizon.

We have already exhibited the possibilities and opportunities of union. Looking back on the past, I realise that there has been a great deal of friction between the States and ourselves. As you have already seen, perhaps, in some of the proposals I have made, I have consistently looked over the light fence marking off the States within the Commonwealth. We have not yet begun to use the powers we already have which we could exercise together.

There is scarcely a piece of our legislation which cannot be forwarded administratively, directly or indirectly, by the States.

In the same way there is hardly an aim of theirs in which we cannot assist them to some extent—

(A Voice : Stick to your own guns)

Why should there be animosity between yourself when doing your State business, and you yourself when doing your Commonwealth business?

The same citizenship underlies both, the same tasks confront both, the same high aims are enshrined before both.

Remember that each of you is at the same time a citizen of both Commonwealth and State.

You would have to split yourselves in two to find antagonists.

Why should we not always recollect that the same citizenship unites both, that the same tasks lie before both, that the same blood runs in the veins of both.

Plea for national unity

Why should we as State citizens clog the operations of the Commonwealth, or as Commonwealth citizens prevent the smooth running of the wheels of the States. I make no offer to surrender one tittle of the Commonwealth’s constitutional power. I do not ask any State representative to surrender a tittle of State power. No doubt there are parts of the Commonwealth Constitution which require rounding off. Powers are imperfectly given which will require to be completely given.

But still, far from exhausting our opportunities for honest co-operation in legislation, and particularly in administration, we have as yet barely commenced to use them.

Let both Commonwealth and State citizens take into consideration the circumstances of this great continent, which require that the first duty of the people of Australia is to work in harmony in the interests of Australia.

Why should we pull against each other?

Let us deal with all questions involved as questions of business with fair play and in constitutional harmony.

You will then get more value for your money and better results for your labours. Away with pride and self-sufficiency, angry recollections, and local jealousies, Surely then the country will prosper more and the burdens of the taxpayer be lightened.

I am tonight running up the flag of the Commonwealth, with a flag of amity and good feeling, beside our standard of national aspirations. (Cheers)

Let me add this—that nationalism does not belong to the Commonwealth separately, but includes the States and all our local governments. (Hear, hear)

There is only one Australia, and one Australian people.

There ought to be only one Australian policy.

It is not a vain hope or aim that we can yet link all our legislatures together.

They are all your legislatures.

All your Governments are your Government, and of your making.

Above all, beware of those who fear a good understanding between you, as Commonwealth citizens, and yourselves, as State citizens.

You can only be sought to be hoodwinked in that way for some nefarious purpose. Your true interests are the same. You have only your own interests to study, and two sets of your own agents to serve them.

What I aspire to, is a union of parties in this country, which shall enrol every man who puts Australia first—then at last we shall indeed possess a party of union striving for a united Australia.

(Loud and continuous applause)