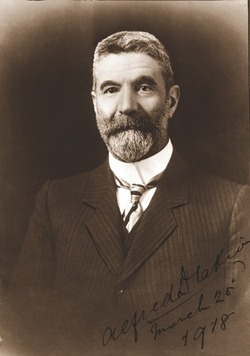

Alfred Deakin was born 3 August, 1856 and died 7 October, 1919. Deakin was the Prime Minister of Australia on three separate occasions: 24 September, 1903 to 27 April, 1904; 5 July, 1905 to 13 November, 1903; and 2 June, 1909 to 29 April, 1910. He was Leader of the Protectionist Party 1901 to 1910 and of the Liberal/“Fusion” Party 1909 to 1910. Deakin represented the electorate of Ballarat, Victoria 1901 to 1913.

Elections contested

1903, 1906, and 1910The responsibilities of this occasion are such that I shall not be able to spare you as I would otherwise desire tonight, because it will be my duty however imperfectly, though at some length, to call attention to the number and magnitude of the interests over which you have control. (Hear, hear) Having to make a choice between serious omissions, and perhaps wearisome prolixity, I have chosen the latter, remembering the admonition that of the two less grievous is the offence to tire your patience rather than mislead your sense. (Applause)

The Australian Commonwealth

I wish to remind you of the vast area on which it is necessary that you should keep your attention when considering the issues which will be submitted, or the story that will be told to you of what has been done. You have to recollect how vast and how varied—because vast—are the circumstances of this continent. (Hear, hear) From the perpetual summer of New Guinea to the spring in Ballarat, now in its blossom, and in Hobart, where the buds are scarcely beginning to break, from the place where I speak to you tonight to Perth, where the sun has yet to set, the Commonwealth flag flies over it all. (Applause)

You will misjudge your obligations if you allow that to pass from your minds. A continent of 3,000,000 square miles, containing nearly four million of people scattered in a fringe upon its outer rim—a country whose increase in the matter of population is extremely small a country whose birth rate at present is low; a country which we hold, but of which we only occupy a fraction, and of which we as yet use but a minute fraction, these are fundamental facts to be burnt into our memories and maintained there for the purpose of interpreting what the Commonwealth is, and suggesting what Australia ought to be.

The federal past

Less than three years ago Australia was sub-divided into six small communities within separate territories completely independent of each other. The subdivisions still remain for many purposes. A great deal of local feeling still persists, but we have now entered into a political union, which we are trying to make, and mean to make, a real union. (Applause)

The key to its future development may perhaps be found in its financial relations. So far the Commonwealth, which collects a net Customs revenue of £11,500,000, is returning to the six subdivided states from £7,000,000 to £8,000,000 a year, and that in spite of the fact that the last few years have been most unfortunate. The drought has devastated the interior, destroying tens of millions of sheep and millions of cattle, ruining thousands of settlers, and driving them back upon the cities and towns. That we should have sustained such serious calamities, emerging with increased energies and hopeful forecasts, affords a proof of the marvellous recuperative powers of Australia.

It was a misfortune that federation should have come into existence just in time to be overtaken by these trials at their culminating height. This fact is often forgotten by our opponents in party polemics. The Ministry have been blamed for the drought. We may on the same method be entitled to great praise because bountiful rains have fallen since we took office, and might assert that the good times coming are our achievement. (Laughter) I put these remarks regarding the magnitude of the continent in the forefront, because I trust that these broad and fundamental physical facts will remain in the forefront of your reflections. If as yet we have done little to deal with the aridity’ of the interior, the reproach for this does not lie at the door of the Commonwealth.

Commonwealth and states

Turning now to the political arena, you have in the last three years witnessed a revolution not yet completed, but far advanced, by which from being simple citizens of one of these subdivided communities you have become citizens of the great Commonwealth. We have made giant strides towards a new organisation of our politics. The rate at which we have advanced has been like the speed of an electric railway or a motor car. Of course, that pace cannot be continuous. It is already slackening off. In the future Parliament will probably settle down to a normal rate. In the meantime we are scarcely conscious of the changes accomplished, because most of their effects have yet to be perceived.

It is claimed that many of you have not yet mastered the difference between the powers reserved to the Commonwealth and those of the states, and each is frequently criticised for the acts of the other. The Commonwealth was in a sense carved out of the states. What was given to it was taken from them. The process of such a transfer is necessarily painful. Friction was inevitable. There have been growing pains in the Commonwealth; there has been perhaps occasionally the fretfulness which accompanies teething, but a little patience will help us. All the federal powers need not be exercised at once. Every state authority need not be hostile to the newcomer. (Applause)

Happily as yet we have little to regret, but we have still a good many rocks to avoid. Despite all appearances we must never forget that there is no severance of interests between the Commonwealth and the states, and there could not be. (Hear, hear) We both serve the same people, pay from the same pocket, and help or hinder them towards the same aims. I plead, therefore, as between them for constant co-operation, for mutual aid and unity of purpose. Gradually we shall disentangle some of our powers. We can never disentangle our common interests. They must be perpetual.

The ultimate question for each of us is, what is best for the people; what do they believe best for themselves; how can we conjointly advance their interests? In the meantime we must keep the bargain embodied in the constitution, fulfilling every tittle of it, not in strained interpretation, but in its plain meaning. The Commonwealth must be true to itself and to the people who created it. It was established to act for itself, not as a mere collection of states or for them, but, as a unit—a nation. It must not suffer itself to be subordinate to local aims, but it must also be true to the states, who are its partners in many things, its yoke-fellows in others, and its allies in all. (Hear, hear) In none of their reserved functions are the states its creatures. What we have now, and what we should determinedly preserve, is an indestructible union of indestructible states. (Applause)

The first Federal Ministry

Before considering the inferences to be drawn from these general principles, and the fundamental facts of our situation. it is necessary that we should cast a glance at the work the first Federal Parliament has done. You have had a Federal Government for less than three years. A month ago it lost its leaders in both Houses, and, shortly before it parted with one of the strongest personalities in politics. (Applause) The choice of Sir Edmund Barton and Mr O'Connor as justices of the High Court has been unanimously approved by all parties in all the states. (Hear, hear) That is a testimony to the splendid careers by which they have attained so magnificent a tribute of public confidence. The loss of all three of our late colleagues was deeply felt. They were all my personal friends. None of us would have willingly parted with any of them. They left us at the call of duty.

Sir Edmund Barton’s resignation

It here becomes my duty, avoiding as far as I can controversial politics, to take notice of a specific charge levelled against the present Government by the leader of the Opposition at Bendigo the night before last. He said, “Against the new Government he preferred a charge of having deliberately squeezed the late Prime Minister out of office when he wanted to stay.” Here was another sentence from his speech;– “Be believed. Sir Edmund. Barton would have stayed at his post if his Victorian supporters did not feel they could not face Victoria with him.” (Shame) I have to say in the clearest, calmest, and most emphatic manner that there is not one jot or tittle of truth in either of those accusations. (Applause) In plain Saxon, they are absolutely false. Not one Member of the Ministry, not one Victorian representative in either House, desired the retirement of Sir Edmund Barton. We all most reluctantly consented to it. (Hear, hear)

Of the present Ministry I will say little. No less than five of the existing states are represented in it by men who have held office as Premiers of their states for years. For the rest, and for all of us, we are willing to be judged both by our past and by our present, and are confident that, with fair criticism of our actions by the people of Australia, we have nothing to fear. (Hear, hear)

The first Federal Parliament

The Parliament just about to be dissolved has had a remarkable history. It lived only two and a half years, of which it sat in session for two years. It was 18 months continuously engaged in its first session. It has had but one recess. At least it can be claimed that it has been both invincibly courageous and laboriously hard-working from first to last. (Hear, hear)

Under the Constitution one half of the Senate require to go to their constituencies—the states—prior to January next. It was to save the Commonwealth the cost of holding a second election for the whole of Australia, and for absolutely no other reason, that the present House of Representatives has consented. to part with six months of its life. (Applause) I venture to say that there are few similar sacrifices to be found on record here. The mere tale of its achievements would occupy me longer than care to detain you. It accomplished one of the main purposes of federation by, at the earliest possible moment, establishing freedom of trade between the different states of the union. (Hear, hear) The Minister of Trade and Customs has been for some time, and, still is devoting himself to the task of making that freedom as ample as possible. If he does not succeed it will not be for want of anything that he can do, but because some of the states have insisted on the letter of their rights.

In addition to this, it has taken over three departments from three states, the Post Office, Defence, and Customs. Each of these was administered under a separate Act in each state. We have now welded the eighteen into three new Acts, thus establishing an uniform administration throughout Australia. in addition to that, four new departments have been created and brought into working order. All of these, so far as the employed are concerned, have been brought under the scope of the most advanced public service Act of Australia—(hear, hear)—protecting its public servants in the discharge of their duty from improper interference, and closing the door altogether against political patronage. (Applause) These would have been sufficient labours for many sessions of past Legislatures. It is but one of the great works accomplished during the existing Parliament.

The High Court

A High Court has been created, which, when its routine has been arranged, will prove to be a source of economy to litigants in all the states who require the protection of the federal law. That court was established in a manner which places it high in public estimation and secures it in popular confidence. It will be the arbiter of many delicate and difficult issues between the Commonwealth and the states. It is the final interpreter of the Constitution; the safeguard of that measure which by your votes you have made the supreme law of this country.

It will be the duty of the High Court to preserve that law from encroachment or attack from any quarter. When we have added an Interstate Commission of economical type we shall have absolutely completed the constitutional machinery embodied in the Constitution. Consequently, if it had done nothing else but established the splendid machinery of administration and of justice, the past Parliament would have earned the gratitude of the people of Australia. (Hear, hear) I have scarcely commenced to note its many triumphs, and can scarcely do more than name them.

Take, for instance, that political basis for all future Parliaments of the utmost importance which is now being. brought under your own eyes. We have on the statute-book the most liberal electoral law ever devised on this side of the world. If there is anywhere else a more liberal electoral law I do not know of it. (Cheers)

It confers, not only upon the manhood of Australia, but upon the womanhood of Australia —(cheers)—the fullest rights of citizenship. From this time forward the women of Australia will have an opportunity unparalleled in history to step into the arena of public life. Hand in hand with us they, will make their share in controlling its great issues better than it has been before. (Cheers)

As you are aware, the method of election is the simplest that could be devised. It is being administered at the present time under the pressure of extreme haste and emergency and without prior experience. It is new to all states, and has in consequence aroused alarm as well as inquiry. This was inevitable under any new electoral law. It is our misfortune that, in order to accomplish the saving of the cost of a second election in a few months, we have had to bring it into immediate operation over the whole Commonwealth, amidst innumerable difficulties and misconceptions arising out of the six laws and practices it has superseded.

The electorate boundaries

Mainly elsewhere, the action of Parliament has been condemned because in this emergency and under pressure of haste we retained the divisions into electorates which were made by the state Parliaments before the Commonwealth came into existence. The Electoral Act as we introduced it provided for three commissioners in each state who might have checked each other, but it was amended so as to provide for only one commissioner in each state. These commissioners fell into the error of mistaking the temporary movement of population from the drought-stricken districts of the states to the towns as permanent. Consequently for the states of Victoria and New South Wales one new constituency was given to the metropolitan districts, while the country was deprived of one representative. The Government took into consideration these exceptional circumstances, and owing to the want of time before the election decided to fall back upon the state constituencies. Events are favouring that action. (Hear, hear)

It is too soon to speak with absolute certainty, but it may be as well to point out that. The metropolitan districts of Sydney, which were to be given an extra member, have had in five of them 34,000 objections lodged to names appearing upon their rolls. On the other hand, in the three country districts, which were most severely tried by the drought, there have been already 7,500 applications for the registration of persons whose names have been omitted. Of course, we must wait for the final figures before passing judgment upon, this matter, but already this great difference is shown between five Sydney constituencies and three in the outlying country. We can see that there was reason for the belief of Parliament that the movement to the cities and towns is being balanced by a movement back to the country; and, with a good season, we believe the wisdom of the action of Parliament will be demonstrated.

An economical government

Owing to the exceptional seasons, the consideration of financial measures has taken up a great deal of the time of the Parliament. Questions of economy have been continually closely considered. I think you will all rely upon the Treasurer (Sir George Turner)—(cheers)— to properly administer that department. He will tell you the plain tale of our financial operations, at an early date. Meanwhile you may be warned against the hasty comparisons of critics who are at best imperfectly informed of the true position of our finances. You know that attempts are being made to compare the expenditure of the Commonwealth with that of the states just before federation. The usual practice is to take one department, as it is under federation, and compare it with the cost of the six departments before federation. Nothing seems fairer on the face of it. But many items,including printing, advertising, rent, railway passes, postage telegrams, repairs, furniture, and other charges, which are charged against the Commonwealth department, did not appear against the state department.

Another method of comparison is to contrast one of the years of the Commonwealth with the year immediately prior to federation. But it has to be remembered that the Commonwealth absolutely closes its books on June 30, while in Victoria and some of the other states it has been the practice to allow accounts to be sent in two or three months after the close of the financial year, and then charged afterwards back to that year. Therefore the state expenditure of the year prior to federation as given represents only ten months, while the Commonwealth expenditure is for twelve months. In the first year of the federation it would be necessary on this account alone to add £50,000 to the state expenditure before a fair comparison could be made.

The present Parliament has properly received credit for its unflinching determination to economise in every direction. It has cut down the cost of the Defence department by £111,000 a year—(cheers)—but even that sum represents only part of the real savings. In the year preceding the Commonwealth a great many officers and men of our forces were in South Africa, and were paid by the imperial Government. They cam back when the war ended and had to be provided for. Then just before federation was a time in which an increase of armaments and rifle clubs was undertaken; These were authorised, legalised, and commenced to be carried out, but they were not paid for until the Commonwealth took over the Department. They appear consequently in the Commonwealth Estimates as if they had been inflated by a new expenditure on the part of our Parliament, whereas as a matter of fact we were simply paying debts incurred in the time prior to taking over the department. his involves no censure on the states: the extra burden simply happened to fall on the federation. If you add the large extra cost thrown upon the Commonwealth by these increases, properly made during the state time, and not charged because they could not be charged, you will find that, while our saving on the estimates is £111,000, the saving actually made is very much larger.

Customs and Postal finance

We have kept the Customs expenditure practically at the same figure as under the state. Then the Customs department in New South Wales had to be considerably enlarged to come up to the standard of the rest of the Commonwealth, and the whole of the entirely new and difficult work of granting the sugar rebate throughout Queensland and the North of New South Wales has been undertaken by. the old, staff without increasing the total expenditure. Consequently, though the fresh work thrown upon it only only resulted in an increase of about £5,000 on previous expenditure, it represents many times £5,000 in the new work done. (Applause)

The Post-office represents in figures an increased cost of £186,000 a year. Yet that increase, large as it may seem, is explicable in the simplest possible manner. In the first place, in Victoria the state Parliament passed a law which brought the penny post into operation in the time of the Commonwealth, and that lost us nearly £70,000 a year in revenue, besides the extra cost of administration involved. In addition to that, there has been the Pacific cable construction, which I by no means regret, but that was authorised by the states prior to federation, and at present it is costing us £30,000 a year.

In addition, the Commonwealth Parliament took its share of responsibility when it cheapened the telegraph rates for all Australia, and made it now as cheap to send a telegram from one corner of the Commonwealth to another as it was, within some states. (Applause) We sent 671,000 more telegrams in our last record than in the time before these reductions, and the extra cost was £65,000. The money was wisely spent. It has made the unity of the Commonwealth telegraphically a reality. But these various sums altogether (remembering also the increased work that has been brought about, necessitating £25,000 this year on new wires) show at once where the increase in the Post-office estimates, and some apparent decreases in its revenue really comes from. We have equalised the pay of the ledger, we find that one hundred thousand pounds comes from the state, and not Commonwealth legislation, and the rest from Commonwealth legislation. (Cheers)

New departments

The four new departments are economically administered. As no comparison was possible between them and the state departments, I asked the Treasurer to take me out the salaries of the nine chief officers in these departments and officers occupying similar positions in this state. The nine Commonwealth officers, without pensions, excepting those inherited from the state, receive £5,500 a year. In this state they received £8,000 a year, in New South Wales £9,000 and in both cases they have pensions. Consequently, considering that our officers are dealing with the whole of the Commonwealth, and these are dealing with the two greatest states, I think the comparisons may be pronounced not unfavourable to the Commonwealth. (Applause)

Cost of federation

To put these matters into a nutshell—what has the federation cost? In the first year it cost 13d per head; in next year bang went another farthing. This year it is considerably swollen, because we have had to throw upon it the whole cost of the elections, £45,000, and £30,000 has also been expended in bringing the Electoral Act into operation, not in one small state like Victoria, remember, but throughout the whole of Australia. Distributing this electoral expenditure as it should be spread over three years, the cost of federation this year is 18d per head. That is the total cost. Is interstate freetrade, is electoral unity, is a national Parliament and Government not worth 18d a year? (Cheers) This year we have £90,000 sugar rebates debited also against federal expenditure. As a matter of fact, the amount deducted from the states before, and therefore the charge is only one of bookkeeping.

The pacific islands

There are also one or two other causes of expense which have to be taken into consideration. For instance, since the Commonwealth was established British New Guinea has come under our control. We are now performing a great work in that country. We are bringing to peace and order districts which were previously devastated by frequent intertribal wars. We shall gradually establish one language in place of the numerous tribal dialects which separate tribes now use. We are dually introducing—or rather, the missionaries, under the protection of the government, are gradually introducing—the principles of civilization, and the industrial arts into that country.

Legislation relating to Papua, as we intend to call it, were laid before Parliament last session. In consequence, however, of certain drastic amendments which were carried, absolutely prohibiting the introduction of alcohol and the sale of freehold of land, the bill was laid aside. The Government is strongly in sympathy with the aims underlying these proposals—(cheers)—but feel that before adopting them they should obtain the views of the resident white population, the missionaries, and the officials who administer the territory. This is being done, and I have every confidence that we shall be able during the next Parliament to introduce legislation that will protect the rights of the native tribes and encourage white settlement.

The interests of the New Hebrides have not been forgotten. We urged the appointment of a British resident, and he is now there doing excellent service. We have pressed for appointment of an international land commission to determine the vexed question of land titles. In that, unhappily, we have not been successful, in spite of perpetual protests and appeals. but we have reason to hope the whole question is now under consideration, and, trust we may arrive at a satisfactory settlement. To maintain the good work the missionaries have done, and to foster trade and settlement, the Commonwealth is paying a mail contract of £2,400, in order to keep ourselves in touch with the group and the British Islands to the north of it. Some anxiety is being caused by rumours that there is a possibility of the resumption of convict deportation from France to New Caledonia. We sincerely trust that these rumours will prove to be ill-founded. So far as Australia is entitled to be heard in this matter—and she has been heard before—the Commonwealth will speak with one voice in opposition to the resumption of so dangerous a practice. (Applause)

New federal departments

In the forthcoming Parliament you must expect that there will be an increase in expenditure, although in many cases this will be represented by a decrease in the state expenditure, so that the people as a whole will be none the poorer, although the Commonwealth accounts are liable to be swollen. For instance, we are to take over the lighthouses and lightships, which naturally require federal treatment. We shall also take over the control of quarantine, an important matter, which at present is under varying systems. These will be transferred, and it may be desirable that there shall be a federal weather bureau, to relieve the various observatories and act for the benefit of both agriculturists and seamen. (Applause) Perhaps more important than all in some respect will be the establishment of federal census and statistics to take the place of the state records, at present some times in conflict, and some of them very obscure.

The federal capital

One purely federal undertaking which must engage the attention of the next Parliament is the selection of the seat of Government. The choice is one of the conditions of the Constitution, and the late Government spared no pains, but pressed on from the first with the necessary investigation of suitable localities. New South Wales appointed a commissioner of high standing, who made a most valuable report upon the sites. This report was well reviewed, and reconsidered by a special board of highly-qualified experts, while many members have visited the sites.

Neither pains, trouble, nor money have been spared to fully inform the public of the merits of the places recommended. Every effort was made to arrive at a settlement by a joint sitting of the two Houses. When that failed, this Government took the question up with earnestness, and dealt with it by bill. For every reason it was kept free from party influences, as it should be, and, I trust, will be. Unfortunately, an absolute divergence of opinion was discovered between the Senate and the House of Representatives, with no present hope of compromise. All that was sought by us was to pass a measure that would enable us to negotiate with the Government of New South Wales for a territory, which would include the site suitable for the future seat of Government.

Unhappily other matters were imported into that bill; questions of area and boundaries, which might well have been left for consideration until a later stage. These would have hampered the negotiations entered into, although they were put only in the form of a direction, and were not made mandatory. In the circumstances, and having regard to these conditions, it was impossible that more should be done in the late session. This question, however, will, require to be dealt with in the coming Parliament, and without unnecessary delay. This should not lead to any extravagance. From the first the very conception of this federal capital has been that it should be built on territory sufficiently large and well chosen which should. provide at the beginning for part and finally for most of the cost of its maintenance. The whole plan cannot be accomplished at once. There must be an initial outlay, but all that is called for now is the simplest and plainest accommodation for the Federal Legislature and the necessary offices connected with its Executive. This could be undertaken at any of the two or three sites named at a cost that will be inconsiderable, and form no burden, on the people of Australia. (Hear, hear)

The idea of the federal capital has conjured up in some minds a vision of palatial buildings, magnificent distances, and a large population. Those may come in time but it will be necessary to make provision for these coming now in the way of providing a sufficient area of territory for the choice of a site. But all that will be necessary at the outset is the germ of a city; the provision of a temporary habitation for those who will have to live there, while omitting everything that might be termed extravagant. This ought to come, and come soon. Indeed, if it were not for the generosity of the people of Victoria in not requiring the payment of rent for the use of the splendid buildings which our Parliament occupies, we should probably find it a cheaper course to transfer ourselves to what is derisively called the bush capital. In answer to this gibe, I assert that the legislation will be none the worse for being carried on in a country district, whose members will sit to consider the interests of Australia as a whole, and of its interior in particular. (Hear, hear)

The trans-Australian railway

Another proposal which has attracted much attention is that for the construction of the railway to the great gold-fields of Western Australia. Some time ago careful investigation of this line was made by the engineers-in-chief of various states, with the result that as accurate an estimate as possible of the cost o this work has been obtained. A survey of the route would be necessary to make this final. The project is one that must appeal to Australian sentiment everywhere, and to the business instincts of those who consider it. Western Australia is now, perhaps, the most prosperous state; certainly in proportion to its population, and no limit has yet appeared to its possibilities of progress. This would be accelerated by its connection with the eastern states.

The engineers calculate that the line would pay in ten years. We will examine their estimate is the confident hope that the outlay will be justified. Not only satisfactory estimates but the consent of two states is required before the line can be constructed. In the one state not only has this consent been given, but a guarantee for a period of years has been offered to the other state against loss, thus proving the spirited confidence that exists in Western Australia in the bona fides of this work. (Applause)

Since I left Melbourne this morning a letter has been received from the Premier of South Australia, informing us that it is not proposed to introduce a bill this session authorising the construction, of this railway. It cannot be constructed without that consent. Consequently we must wait, in the belief. that when they hear and see my hon. colleague—(laughter)—they may find themselves in a more friendly frame of mind onwards what is certainly one of the large Australian projects worthy of the consideration of all our citizens. We would be pleased to find the other trans-continental line approved if it were constructed on fair terms and wise conditions.

Tho South Australian project is for the line north and south through the continent. We cannot have too many means of bringing ourselves into touch with the remote parts of the Commonwealth, whose worth is not yet realised by the states themselves, and certainly not by the people of the eastern states. (Hear, hear) The two conditions are that they should be payable and involve no sacrifice of national policy. Our neighbourhood to the great continent of Asia and its teeming millions is a fact never to he forgotten. The proposal to transfer the Northern Territory to the Commonwealth has been temporarily withdrawn by South Australia. Its finances show no improvement this year. Having this great continent for the first time under one control, it is only natural that we should lift our eyes beyond the states to the furthest corners of our great domains. We have dealt and are effectively coping with some of its greatest problems. Will it not be admitted that the tale of tasks accomplished briefly given is one, to use, a familiar term, that fairly breaks the record.

Patents and naturalisation

The policy of frugality will be continued, but you must not forget that much of the legislation for your advantage lays an extra burden of expense on the Government. We have, for instance, just passed one of the most practical, useful federal acts that the statute-book is ever likely to see. That, is, the Patents Act. (Hear, hear) It will now be cheaper to get a patent for all Australia than it was to get one in five out of its six subdivisions. Allowing for simple plans, we have made it open for inventors to protect their rights throughout the Commonwealth for £20, while with the separate States the cost would have been £120. (Cheers) We unlock to inventors the official reports upon inventions whose novelty is questioned. A great boon to them. But when the estimates show £3000 to £4000 set down next year for a central office, you will be told that this is more “federal extravagance”.

Then, take the Naturalisation Act, which gives every white man liberty to go freely through the Commonwealth. (Hear, hear) The administration of this act will pass from six state officers to the two or three federal officers, who would be necessary to administer it. The people have to inquire, in connection with these transferred departments, whether corresponding savings have been made in the states. If they have, the cost to the public has not been increased. If they have not, it is not to the Commonwealth the people should look. Other measures which will be very useful to the commercial community are a federal banking law and a bankruptcy and insolvency law. These will not involve any administrative expense, but they will help to tighten the federal bonds, and to sweep away existing barriers, costly to business men and tradesmen.

The Maitland manifesto

If you remember the Maitland manifesto, you will see that all the measures promised there have been passed into law, with the exception of the Arbitration Bill, the Interstate Commission Bill, and the Federal Capital Bill. Each of these were submitted to Parliament, and each will shortly be submitted to Parliament again. Only the curtailing of the session for the sake of economy prevented them from being passed. A Federal Old-age Pensions Bill will have to wait till the financial restraints of the constitution have been removed. The experience of the states will then have taught the Commonwealth what to provide, and what to avoid. Such a bill will impose no new expenditure on the people, but will simply transfer the state expenditure to one federal system. It will be undertaken as soon as our finances are free.

White Australia

In this theatre, two and-a half years ago, I laid special stress upon the white Australia policy of the Government. (Applause) After that there was a fierce conflict in Parliament as to whether the means we proposed to exclude the undesirable and colored aliens would suffice. There were those who wished that on the face of the statute the prohibition against them should appear in so many words.

We believed that we studied Australian interests, and also lessened the difficulties of the mother country, if, instead of saying in so many words they should be excluded, we placed in the hands of the Government an educational test which could be applied so as to shut out all undesirables. We have had two years’ experience of the working of our test, and it has worked well. You have seen from time to time how few have managed to survive it. The returns for the last nine months show that 31,000 persons entered Australia from over sea, 28,000 being Europeans. Of the remainder, many of the colored persons came to Australia to engage on pearling vessels. The arrangement we have made is that they land only to sign their articles. A guarantee is taken from those who bring them that, when their time is up, they shall leave the country. By this means they never really enter Australia. They merely fish in our waters or just outside them.

I find that out of 408 Japanese who came to Australia 374 went at once to the pearling vessels; 11 others had been in Australia before, and were entitled to return; while one deserted and managed to escape our clutches. (Laughter) 406 Malays came to Australia to engage in the pearling trade. Only one was entitled to enter the country, and again we had one deserter. 73 Papuans came over to assist in pearling; none deserted, and all will return. To come to the persons who, either under the state law or since, have secured domicile in Australia, the return shows that 2,571 colored persons entered the Commonwealth during the nine months, of whom 2,561 entered under the authority of the law. There were only 10 to whom we could not or did not apply the test. Besides these there were 785 Pacific islanders, who came in under permits which cease on March 31 next, after which no kanaka is authorised to be brought into Australia. (Applause) While 785 came in, 978 went out. There were 755 Chinese entered the Commonwealth, while 1,156 went out. Altogether 3172 colored people left Australia. (Applause)

The alien colored population is being steadily reduced. Now, as to the test. Of course this is not much applied, because ship-owners know that if they bring colored aliens to this country who are not legally entitled to land, they will have the pleasure of taking them back to their native land. During the nine months 121 such immigrants presented themselves; nine only got through. Out of these two were entitled to do so because they simply came from Ceylon to purchase horses, and of the others I find that five were probably colored sailors who deserted from one ship and enlisted on another. I don’t think that during the next nine months even nine are likely to enter.

You probably believe that a white Australia is secure. I hope it is, but it won’t be secure unless a vigilant watch is kept upon proposals to tamper with it. None of a serious character have been put forward by anybody in a responsible position, but there are indications that we may have to defend the principle yet. So far as this Government is concerned it will be ready for the emergency. (Cheers) A white Australia does not by any means mean only the preservation of the complexion of the people of this country. It means the multiplying of their homes, so that we may be able to occupy, use and defend every part of our continent; it means the maintenance of conditions of life fit for white men and white women; it means equal laws and opportunities for all; it means protection against the underpaid labor of other lands; it means social justice so far as we can establish it, including just trading and the payment of fair wages. (Cheers)

A white Australia means a civilisation whose foundations are built upon healthy lives, lived in honest toil, under circumstances which imply no degradation. Fiscally a white Australia means protection. We protect ourselves against armed aggression, why not against aggression by commercial means. We protect ourselves against undesirable colored aliens, why not against the products of the undesirable alien labor? (Cheers) A white Australia is not a surface, but it is a reasoned policy which goes down to the roots of national life, and by which the whole of our social, industrial, and political organisations is governed.

The tariff

One of the great results of the unremitting labours of the Parliament has been the passing of the first federal tariff. Daring the whole of the period while it was being discussed business was disturbed, uncertainty prevailed and trade was paralysed. If that tariff is to be wantonly reopened now, precisely the same conditions must recur. Importers and manufacturers are becoming adapted to it. The public have just learnt to look below that label which used to be put us at first, “Raised in consequence of the tariff,” only to find very often that the article was on the free list. (Laughter) The public, purchasers and traders, have come to understand the tariff, or most of it, and are living under it, to the amazement of some of our free-trade friends, without finding the cost of living enhanced. Yet just at present we are met with the proposal that this tariff is to be torn up, and we are to be launched once more on the sea of uncertainty. A proposal of that kind is neither wise, statesmanlike, nor reasonable. (Hear, hear)

The tariff, whatever its defects, and I don’t deny them, is entitled to a fair trial. At all events, the community is entitled to rest, and the business people to know where they are. (Applause) Of course, the proposition is being steadily whittled down. First, the whole tariff was to go; then all the protectionist duties were to go; now some of them are to go. At last it is a mild tariff revision; it is only a little one. But the question whether the tariff if it begins shall be a little one or a large one, does not rest with the people who propose a little one. That tariff was accepted by us simply because some of the prolonged discussion. For these we sacrificed much. (Hear,hear) This is not the protectionist tariff to which we have been accustomed, and for which we hoped. Some industries have been destroyed by this tariff; some others have been injured, and many have not been assisted. Of course they had, the extra opportunities afforded by interstate free-trade. But for its compensations others might not have survived. If the tariff is torn open we shall of course employ every means we possess to repair the omissions and mistakes in the present schedule of duties. They are numerous. The strife will belong.

Fiscal peace

Relying upon the energy of our people and the operation of interstate freetrade, we accepted that tariff for want of a better. On the same public grounds, putting aside our own desires and beliefs as to what is best, we are prepared to preserve that tariff, because we believe that the best boon to this community that its public men can give it is fiscal peace. (Hear, hear)

The clean-cut issue then in the contest now to be commenced lies between those who hold with us that what we need is time to adjust ourselves to our new conditions without another tariff campaign in Parliament. Experience is being gained of the real operation of protectionist duties in centres where they were taught to expect nothing but baneful influences. The very fact that we are willing to wait and trust to this experience shows our confidence in the working of the protectionist part of this tariff. (Hear, hear) Those who are in haste to alter it before it can be fully appreciated prove that they realise that the tide of public opinion and experience will be against them. They know, and have reason to believe, that it will be easier for them to alter it now than ever again.For the same reason those who cherish fiscal peace, or have faith in the principle of protection, should realize that this is not the hour when we should again commence to tinker with the tariff—to indulge in a wasteful kindling of the fires of strife, when trade is beginning to follow the new channels it has made—and to undo for the purposes of undoing. These are the aims of those who oppose the Government.

When I last addressed you I estimated that at least half a million people in Australia, directly or indirectly, were dependent on the protected trades. That number has now been much increased, and is being increased, especially in Sydney. It is the operation of this tariff which will inevitably strengthen in the future the protectionist knowledge and sentiment of the whole community. Those who are engaged in our industries have no right to see their earnings threatened at the very time they are promised good seasons and revival of business. The tide of prosperity is just beginning to flow and it is indefensible to prevent it by the renewal of fiscal strife. The permanent planks of the Liberal and Ministerial policy are the maintenance of the tariff and fiscal peace. As a valuable corollary we hope to pass in the next Parliament a measure which we were prevented by time alone from passing last session. I refer to the short bill to prevent the growth of rings and trusts in Australia—(cheers)—or if any such exist enabling us to cope with them. We seek protection for the people, and for the employee as well as the manufacturer.

Industrial arbitration

The next necessity for a white Australia will be to pass the Arbitration Bill, to prevent strikes, and lock-outs, and provide for the adjustment of all those feuds between employer and employee by an impartial industrial court, which will give a certain guarantee for the investment of capital, and for the just treatment of white workers. (Hear, hear) This measure will be introduced in the first session of the new Parliament. It was only laid aside on the last occasion because it was perfectly plain that this election must be held shortly, and there would not have been time to pass it through both Houses. If we attempted it we should only have lost many useful measures without securing it.

There will be no alteration of the Arbitration Bill in reference o the servants of the states. It is a question whether the Federal Parliament has power to deal with them, but assuming it has the power, it is not for the Commonwealth by its tribunal, to dictate wages and conditions on state railways. To control a railways to be to control that state self-government which we are pledged to preserve. (Hear, hear) It is not a question of sympathies: it is not a question of desires; it is not a question of willingness. When the time comes for the state Parliaments to place their railways in the hands of the federation then we shall assume all responsibilities. But at present the states, while they finance them, must be left to manage the railways in their won fashion. Those who cannot manage them to the satisfaction of the people should transfer them. Two states already place their railways servants under their arbitration courts. These are excellent precedent. Just as our tariff programme is fiscal peace, the object of the arbitration Bill is to ensure industrial peace.

Navigation Bill

When the Arbitration Bill is introduced the will be no difficulty next session in applying it to interstate shipping and seamen engaged upon it. (Hear, hear) Happy am I to see that an arrangement has been entered into between she shipowners and the seamen that will prevent and dispute for the next six months at least.

(An Elector—"they could not help it")

We shall then be in a position to deal with the difficulties that confronted us last session, because side by side with it, or coming soon afterwards, will be the Navigation Bill, dealing with Australian and other ships plying between Australian ports, carrying Australian cargo. (Cheers) This proposal is no new one. At the late conference in Great Britain, then Sir Edmund Barton represented the Commonwealth, resolutions were adopted advocating two principles. The first was the exclusion f the shipping of countries that exclude us fro their coastwise trade. The other for special preference to British shipping. I agree with both aims. In framing these bills the exceptional position of Western Australia and the plea of its Premier that passengers on mail steamers should be exempted, will be taken into accounts. Whether any action of this kind will be necessary cannot be determined until the contracts for the new mail service have been received january next. The question will then receive full consideration.

Interstate commission

We are looking forward to the time when shipping and railways will be supervised in the public interest, so as to prevent the inequitable treatment of their customers by means of an interstate Commission. The rates on both require to be of a federal character. The bill which we introduced formerly was perhaps more comprehensive than was necessary. It will be the object of the Government now to reshape it on economical lines.

Murray waters

Another matter which may someday come before the Interstate Commission relates to the utilisation of the waters of the River Murray. The Commonwealth is entitled to be heard under its power over navigation. I believe that a proposal was consider at the last Premiers’ Conference, and almost assented to, that the Commonwealth should be asked to act for the states, on certain conditions, in this vexed question. Should any such request ever be preferred, the Commonwealth will cordially accept it. We realise that this is an Australian question, to be dealt with on an Australian scale. If the Murray Valley is to become the centre of the comparatively dense population is is well able to carry, it can only be done by the proper utilisation of those waters which run to waste to the sea.

Iron bounty

Peace is a great gain to all classes, and particularly to business men and those associated with them as producers, but something more than the peace is required for a progressive community. The Government is prepared to unfold a series of positive practical proposals. One of the measure commonly applied to determine the status of nations is the standing of the iron and steel industry. One of the most ominous signs of the times is the falling of the mother country for first to third place in the production of iron and steel.

We in Australia are favoured with magnificent deposits of iron ore, every state has them, and many are extensive. We have a large consumption of pig iron and machinery. Excluding the latter, our imports average £2,600,000 a year, including 32,000 tons of pig iron. We buy machinery to the value of £1,750,000 a year. There are also great possibilities of Australia becoming the centre for an export trade. I believe that on this matter the people will be courageous, although the last Parliament was timid.

To properly establish this industry a bounty will be necessary, and a bounty the Government is prepared to propose. Duties of 10 per cent. are already provided in the Tariff under Division VI [?] contingently upon the establishment of the industry in Australia. We have the assurance that thousands of people can be employed in this industry with very little delay. In the utilisation of our deposits of iron, or in their manufacture and export, lies a great opportunity,, which we hope this Parliament will authorise us to seize. (Applause) This is one of the means by which we can multiply employment and also our numbers.

Need of population

Australia needs an increase in population (Hear, hear) Practically there was no immigration in the last decade prior to federation; its diminution is not due, therefore, to anything that federal legislation has done. Immigration has practically ceased. The movements from state to state are not distinguished in the returns I have been able to examine. But at all events it is plain that a most unfair and vexatious use has been made of the statistics dealing with interstate exchanges of population. During the nineties this state was hit heavily by bad seasons, bank failures, commercial crisis, and depression in mining. In addition, the golden West opened its treasures, and our population was tempted there. In these circumstances Victoria lost heavily. She had been losing for some time before, simply because the amount of Crown lands available for selection did not suffice for expanding families of our farmers. Numbers of families left Victoria because they were offered larger areas for themselves and each member of their families.

If you want to study this question you will only to look at two tables, namely, the mining figures in the several states, and the alterations in the land laws among our neighbours. They show that when the immigration is stimulated afresh, and where it goes. There is no sign of fiscal changes exercising any influence. An attempt has been made to wrest the figures to serve a fiscal argument. let me take the term of office of the Leader of the Opposition, who persistently and unfairly employs this fallacious argument. He was Premier of New South Wales from 1894 to 1899. With the assistance of the Labor party he carried free trade, and trumpeted its benefits in every state, and win all parts of the world. The whole world know that while the rest of Australia was protectionst New South Wales had become free trade, and all the world was invited to share its treasures. How did the world respond? During his five years of office New South Wales lost 1,882 persons. (Laughter and applause) Was that due to free trade?

Look at the neighbouring states. I won’t take Western Australia, were the growth of population was due to mining. I will hardly take little Tasmania, which gained 5,600 people, as, perhaps, that was due to some extent to mining. Queensland had no mining boom, yet she gained 13,000 in population, and was under a tariff termed protective. Let us take a radical state—let us take New Zealand. While New SouthWales lost 1,800 souls, New Zealand gained 13,700. So when we hear the fiscal arguments out in connection with population, let somebody ask an explanation of this increase.

(A Voice—"what about Victoria?“)

Victoria lost 82,000 people during the decade, while Western Australia gained 94,000. I don’t want to look at this question from the fiscal point of view. It has no real relevance. I am at present dealing with a bigger problem. I want to find the reason why ‘Australia as a whole whether under free trade or protection, is falling behind in the matter of population.

(A Voice—"Too much government”, applause)

If you had too much government it was in six different pieces. The total Australian gain for the last ten years was 28,000, or less than 3,000 a year,and in the same time the gain in New Zealand was 31,000. Little New Zealand gained more than the whole of Australia. That cannot be explained away on fiscal grounds.

(A Voice—"Too much legislation", applause)

New Zealand passed more legislation than any state in Australia. Apart from all such theories, is it not perfectly manifest that a gain of 28,000 in ten years is utterly inadequate in a great continent like this!

The states and immigration

Then remember I am not propounding a federal question only. It is a question which concerns the state Parliaments more in one sense than the Federal Parliament, because the states control more factors whose handling can attract population to the Commonwealth. In addition to the loss I have referred to, there has been a grave decline in the birth rate. Our new senator (Dr. McKellar) is presiding over a most necessary enquiry into this delicate and difficult circumstance.

A white Australia is not possible without whites. Where is Australia to obtain white men and women if we neither produce them ourselves nor attract them from abroad. (Cheers) Look at the matters which lie within the control of the states. They own the land, and land is the great temptation to new settlers from the old world. They own the mines, and the mines have helped to make the reputation of Australia. They own the waterworks, which determine a the distribution of settlement in many districts. They also own the railways, by which the land has been opened up. They control all these factors. (Cheers)

In the United States the Government owns the land, and there is now proceeding in the western states of that country one of the most gigantic operations in the sway of settlement ever witnessed, the reclamation of hundreds of thousands of acres of what is desert land by means of the utilisation of the water resources in its neighbourhood. This is being undertaken by a Federal Government, but we a have not under the Constitution any power to make a commencement in such a work. Consequently when you consider the need for cheap land, for liberal mining laws, for an efficient water supply, and for low freight rates, all these must be obtained from the state Legislatures. The Commonwealth may co-operate with them, and will do so to the utmost of its power. We want white people; we want them on the soil.

The six hatters

I have waited rather patiently for someone to call out for the six hatters. (Laughter) Interest appears to be diminishing in these interesting gentlemen.

(An Elector—"Mr. Reid is sick of them. They are dead.“)

I have told you what the immigration into Australia was before the Commonwealth came into being, and before the act in which the contract-labor clause was inserted. Australia had practically no immigration then, and if she has no immigration today, she is no worse off because of the Commonwealth Legislature. There is a much more stringent law against contract laborers entering into the United States, but it has not prevented that great country from receiving the largest and most constant stream of immigration ever known.

As I said before, 31,000 people entered Australia during the last nine months. That does not prove that we have gained that number, because I have not vet obtained the figures of those who have left. Taking the fact that we gained 2,800 the year before federation, I think it is clear that we are at least gaining as much since federation. Now what was the object of the condemned clause? Simply to prevent men being brought here at lower than the ruling rates of pay in order to displace men receiving those ruling rates of pay. (Hear,hear) It is no gain to the community to see one set of its labourers being replaced by others. Probably, too, the men who entered into the contracts were unacquainted with the rates of pay or conditions of work in Australia.

We are told that this same protection should be given in another fashion. We are willing to listen to such a proposal. It appears to be admitted by those who are criticising us, including the Opposition, that some provision of this character is wise. Let us, then, look at their proposition. If it fulfils the need efficiently we will consider it, but we would like to see in plain terms the clause proposed before we commit ourselves to what appears to be an attempt to take advantage of an incident which never would have occurred if the plain precept of the law had been obeyed. I am perfectly well aware that the misrepresentation of this incident has done us harm abroad. If it has not done more harm it is not for the want of iteration and reiteration here and elsewhere. (Hear,hear)

We want all the white people we can get who are fit to colonise. We want and welcome them. But the fact remains, which cannot be denied, that as yet, although the contract labour clause is in existence, there is not a human being on this planet who has been shut out of Australia in consequence of it. Six hatters in one case and three engineers in another have been detained for examination, and when it appeared clear that they were desirable colonists, and there was work for them in the states, they were admitted. Not one man or woman can be pointed out who has been turned back on account of the contract labour clause. (Applause) That should be given a little prominence when we know what has been said of the six hatters, whom the people of the old country probably believe have been hung, drawn, quartered, and perhaps crucified, directly they arrived in Australia.

The tariff and population

Granted that we need more suitable settlers, will shutting up factories and discharging artisans assist population? Will removing duties on the farmers’ produce enable us to increase our population? The time of stress during the drought was severe enough. Thousands of farmers were driven from their homes, but how many thousands were able to remain and encouraged to return to their homes through the assistance afforded by a protectionist tariff?

Even in a time such as this we have maintained our population owing to the federal tariff, which has also been the means of renewing the population on the soil. We can also claim, particularly as regards New South Wales, that this tariff has been the means of increasing employment. We do not claim that the duties are scientifically adjusted, but they are partially adjusted to suit our needs, and we can cure the defects hereafter. What else can we do to encourage population, particularly with regard to settlement on the land?

It appears to me that the time has come when the Commonwealth should endeavour to do its share by encouraging rural industries. This could be done by offering rural bounties. There are products which should be cultivated in the southern states, and there are others—such as coffee and cotton—which might be cultivated in sub-tropical Australia. These would give employment to white people, and to their children after them. In the United States the Agricultural department lends valuable assistance to all forms of rural industry.

It will be possible by thoughtful inquiry and judicious action to lend assistance to agricultural and pastoral pursuits, to horticulture, to viticulture, and all those industries which we have only been able to reach hitherto through our fiscal policy. Our aim will be to build these up. The iron bounty will be of much assistance, while the establishment of bounties for agriculture can be made to foster rural development generally. We do not wish to override or interfere with the state Agricultural departments, but we may be able to focus their work and give them valuable help. We can do this without the creation of a huge bureau.

Already the Commonwealth has endeavoured to assist the export trade of Australia. The new mail contract fixes maximum freights for the the carriage of meat, butter, fruit and rabbits, for the best known refrigerating machinery tested by self-registering thermometers, and a penalty for damaging fruit by careless treatment. (Hear, hear) Probably we shall be able to encourage by counties the best method of placing our perishable products on the market of the world. Especially we want to increase that trade with Great Britain. (Cheers) We want more British settlers. We want more British users. We want preferential trade. (Loud cheers)

Conversion of debts

But before I deal with that let me digress for a moment to take another issue, which I have often discussed with you. It is the question of the debt so closely related to that of population. (Hear, hear) Do you know what the debt of Australia is? The Commonwealth owes nothing, cause it has borrowed nothing. (Laughter) I am almost tempted to say I hope it never will. (Cheers)

Still we represent the people of Australia, who owe £200,000,000 through the states. Remember even if, as proposed, those data taken over by the Commonwealth they do not cease to be state debts, as it is the people of each state who have to severally indemnify the Commonwealth, and pay interest on all that is taken over. You owe £200,000,000 through the states. How do you propose to pay it? The object of the Commonwealth taking over the state gets is that it should act as broker, and by creating one Commonwealth stock and watching the market, takes favourable concessions to reduce the interest you have to pay. (Cheers)

The Commonwealth can make no profit for itself but it will make a profit if it can to secure a great saving the people of Australia. (Cheers) But, as I have told you a good many times, you can expect any savings from the Commonwealth while the states continue to borrow just as they please in the future. (Cheers) That would only mean putting a 7th borrower on the market in the name of Australia, and that would rally injure them help you. I cannot enter into this question deeply, because there is soon to be a conference between the Commonwealth and state Treasurers and hope that the gravity of the situation will then be realised in regard to the debt, as well as in regard to the population.

The greater the population the lighter of the debt burden; the smaller population the heavier the debt burden. And what is your debt burden? I find we are required to pay 8 millions a year borrowed money. Part of that is covered by reproductive works, but a good many government works are very fractionally reproductive. (Laughter) In addition to that it is estimated that we pay at least 5 millions annually on private securities. This makes 13 millions a year on borrowed money. It is a heavy sum to find annually, and very important, not only in regard to population, but in its bearing upon protection, as maintaining population and employment. I regard preferential trade as an admirable accompaniment of protection for increasing population and employment.

A high commissioner

Our interests are very closely bound up financially with those of the mother country, because of the huge debt we owe in London, and because of the huge business we do in London, and because of our diplomatic interests which require to be safeguarded in London. The Commonwealth has to be represented in Downing–street, in Lombard–street, and in markets of Covent Garden. Consequently Commonwealth representation is necessary in London to supervise these great interests; to express our political views; to keep in touch with financiers in dealing with Lawrence; to draw us to minimum women of British blood; and to disperse into thin air all such terrible fables were found upon the “six hatters”. The more we export to London the more we want a High Commissioner on the spot. There is a golden opportunity presented to us such as has never been presented to Australia before, and it is presented to us in such a way that we can secure by this means not only more hatters, but more farmers, graziers, fruits–growers, and cultivators of the soil. We will have more exports, to send to London, instead of sending our money there.

National trade

I do not propose to discuss the politics of the mother country. We have enough to do to discuss our own. (Laughter) But we see in Great Britain a conflict between two great parties, while the same conflict exists here. The one party asserts the trade knows no flag; has no patriotism; its sole criterion is price. By whatever is cheapest were a viewfinder, and you have the golden rule. By whom it was made and under what conditions of trade and questions to be asked. Your only enemy is the man that sells cheaper than you do.

The other doctrine has recently been expanded with superb force, simplicity and admirable cogency in a little pamphlet by the promised arrangement, Mr Balfour. (Cheers) As he puts it, there are considerations before cheapness. There are natural interests superior to it. We endorse this doctrine heartily. Our maxims are that trade is a powerful tie making for unity; That common investments make common interests; strengthening asks when built up within the Empire, and weakening us when transferred to our rivals.

As a man’s first duty is to provide for his own family, it is a statesman’s first duty to provide to his own people. No nation in the world has feared to raise its protective duties against Great Britain; but now we are told Great Britain should hesitate to raise its duties because of the danger of reprisals. Are we then so much more at their mercy, so much more dependent upon them than they are upon us with all our commerce. Our conviction is that we are free enough and powerful enough to protect ourselves without asking permission. We do not look only to price. The new economy looks to honest ways, truthful labels, fair wages, and the distribution of profits of barter as far as possible among our fellow citizen. It is national as well as human.

Foreign trade

Free–traders hitherto had greatly objected to any other title, and especially resented the appellation of foreign-traders. Now they are forced out into the open. Their affection to the mother country has disappeared. They are foreign–traders pure and simple. (Applause) We offer to Great Britain preference in our ports, but this is refused by our opponents, simply and avowedly in the interests of foreign imports. They are therefore more his friends than those of the Empire. They are foreign–traders, naked and unashamed. They are also creatures of inconsistency. (Laughter)

Though always advocates of commercial treaties, they now object to make them with their own kith and kin. They favour treaties which contained the most favoured nation’s provision, but we must not make most–favoured-nations of our own flesh and blood. They believe in reciprocity, provided it is not within citizens who live under the same flag. For for the sake of the foreign trade they are prepared to sacrifice all these. Between the two policies, Australia will surely not hesitate. Is it national trade or foreign trade? National trade, say the Ministry; foreign trade say the Opposition. (Cheers)

We are told not to mix sentiment with business, and to keep as far aloof from the mother country as we can, treating her only as the rest of the world in case we should quarrel about terms. Why did they not say so in discussing the naval agreement? Was not that a business bargain? Was not the question of costs carefully considered, the amount of payment well thrashed out and examined? Was not that a temporary agreement for a fixed term? Did we not come after considerable business discussion to what was deemed a fair agreement? Did we not after all these business considerations allow sentiment to have some sway? If not, why do we not follow the foreign trade maxim, and put our naval defence up for tender, so as to let foreign nations compete? What is the difference between a defence agreement of that kind and defence against industrial war? Are there not industrial conflicts which destroy homes, ruin industries and depopulate whole districts? If we unite for martial and naval defence, why should we not unite for industrial defence against the whole world? (Cheers) When our men volunteered for service in South Africa did they volunteer upon a business basis?

(A Voice–"They did not know what they were doing")

We know perfectly well what they were doing, and the world knew what they did. (Cheers) When we have seen wars waged for bond–holders, and wars now threatening in the East for the commercial markets, wars, with all the horrors, losses, and expense of blood and treasure for commercial interests, should we not strive to protect industries, our wage-earners, our manufacturers, and our trade. (Cheers)

Preferential trade and protection

If the Empire is to advance, it must be by the advance of all its parts. It is too huge, scattered, and diverse in conditions and character to be treated as a single unit. We are told by the foreign trader that to speak of self-development in parts of the Empire is a doctrine which is selfishly Australian. Well, the late Secretary of State for the Colonies, and the Prime Ministers of all the overseas possessions, met in London last year, and by resolution declared that free trade within the Empire was impracticable, and that each of the dominions must look to its own development. We are pursuing the lines laid down in these resolutions when we seek to make Australia a part of the Empire, whose trade is worth having.

A protectionist tariff is essential to Australia, but there is nothing in that antagonistic to close the trade relations with the mother country. It is true patriotism which trades with its kindred and prefers its own productions. I was present at an Imperial conference held in London in 1887, when Mr Hofmeyer made a most statesmanlike proposal. He suggested that the duty of 2 per cent. should be levied by Great Britain and her dominions upon all foreign goods. It was calculated that from that small duty revenue of some £7,000,000 would be obtained annually, which could be devoted to purposes of general defence. (Cheers) Not felt by the Empire, not felt by the colonies, and paid by the foreigner, it would have enabled us to protect ourselves against the foreigner. (Applause) Heartily supporting the proposal then, I support it still.

Mr. Chamberlain’s scheme

There are more modest proposals before us now from Mr. Chamberlain, who has defined them with characteristic courage and resource. He has said that in his opinion there should be 2/- duty on foreign corn, and no duty on British corn from British possessions, a duty corresponding to that on corn or foreign flour, a five per cent duty on foreign dairy produce, except perhaps bacon, and a substantial preference on wines and perhaps fruits. Now, what does he expect in return ? He expects the British dominions to grant preference to Great Britain, and we are prepared to do so. (Cheers.) He asks to be authorised by the electors of Great Britain to make these, or similar propositions to us, and he will then make specific propositions as to the staples of British manufacture in respect to which he desires Australia to grant preference. When these proposals are made they will receive most cordial, most hearty, and most generous consideration at the hands of any truly Australian Government. (Cheers)

Wheat preferential trade yields

Now, what does this offer mean? The present English import of wheat averages 170,000,000 bushels per annum, though only 57,000,000 bushels come at present from within the empire. In Canada, Australia, and South Africa are granaries that surely ought to supply the whole demand. If they did, what would be the position? At present Australia sends 32 per cent of that 57,000,000 bushels. Supposing the empire supplied its own wants in wheat, and Australia increased its export, and sent 32 per cent of the whole British consumption, it would mean we would require to grow, and have a market for 38,000,000 bushels more than the largest crop we have ever harvested. To produce those extra 38,000,000 bushels would employ thousands of farmers, millions of acres would improve husbandry, and give us a splendid market and income. Our full share of the butter industry, calculated in the same manner, would be almost as valuable a gain as wheat. The two together would mean an enormous increase of population, unemployment, of agricultural settlement, and of wealth.

What can we offer in return, and do we need to offer something now? In 1801 our imports from Great Britain were £26,453,000, and in 1901 £25,237,000, a decrease of nearly £1,500,000. Some of these would be transhipments of foreign goods. In March, 1891, other British colonies sent goods to the value of £4,329,000,and in 1901, £450,000 worth more, while foreign countries sent goods directly to the value of £6,027,000 in 1891, and £12,412,000 in 1901. They had nearly doubled their export to Australia in 10 years. Now, it may be perfectly true that the whole of that 12 millions does not consist of goods which the United Kingdom or even the rest of the British dominions can supply, but even -so we have a considerable margin.

Having regard to its dominions in all parts of the globe, there can be very little indeed that the empire cannot supply. The Empire buys from foreign sellers nearly £800,000,000 of their goods goods each year. Why should not part of is enormous sum be spent in development within its own domains? Our purchasing power would grow with our growth. If today our total imports are 42 millions sterling what would our imports require to be if we exported 38 million bushels more of wheat and dairy produce in proportion? Our imports would advance by leaps and bounds, and this increased trade would find its way to us.

When we are asked to grant preferential trade we should be prepared to deal with the proposal in a generous spirit the items asked maybe at first few, and for a term of years, but they will be capable of readjustment and being multiplied. We must follow the example of that most enterprising and capable leader, the Premier of New Zealand, who has always been fully alive to the interests of his colony in this matter. (Hear, hear) He has realised in advance of most of us the advantages to be gained by preferential trade, and has stepped forward to fulfill them. It is impossible to foretell how this reciprocity may develop, but besides Great Britain. there are splendid prospects for our trade with South Africa, which, however large it may have been, can be made much larger. We might help New Zealand to share that trade, of which so much now goes to the Argentine.

What preferences are given

We are told that the preferential proposal is a selfish one. What did the South African federation do, whose preference has been warmly welcomed by the mother country. Before giving preferences the South African federation raised their duties 25 per cent, and then gave Imperial preferences to the same amount conditionally upon similar concessions from other dominions. If Australia could take the same step it would be equally applauded. The Canadian preference has been censured as ineffective, but only by those who have not studied the question fully. The replies of the Dominion ministers proved that it has doubled its purchases of British goods. It was also conditional. When Mr. Chamberlain made his proposals the Australian Government would be prepared to treat them generously item by item, considering all the circumstances and the importance of the industries to the Commonwealth. If we are offered such a boon as his tentative scheme promises, we can afford to look with a liberal eye at the concessions which are asked from us. (Hear, hear)